请 更新浏览器.

过去几年,美国家庭的经济实力支撑了美国经济的强劲增长.S. 经济增长展望. 随着我们进一步度过大流行时期的储蓄激增, 消费增长正日益与实际收入保持一致. 如最近的研究所所示 现金脉冲 释放, 现金流出接近流入(减缓了中位数余额的下降), 而较小的流动性缓冲为家庭提供的回旋余地比2020年初以来的任何时候都要小.

对实际收入增长趋势的不同看法. 随着需求的前景越来越紧密地与薪酬联系在一起 问题 about what could be driving a deficit of consumer confidence—a lot of attention has been dedicated to what’s going on with the purchasing power of incomes, i.e.,实际收入增长. 对于这样一个基本的经济概念, there is a surprising degree of heterogeneity in beliefs about the extent to which “incomes are keeping pace with price increases.“也许这是自然的. 毕竟, 在2022年年中通胀见顶之后, there was public debate about whether things were looking better due to discrepancies between year-on-year vs. 时间序列中逐月的变化, 一个单一的指标(虽然, 公平地说, 核心与核心的比较. 标题等等也是复杂的因素). 实际收入增长需要两个时间序列(难度加倍)!).

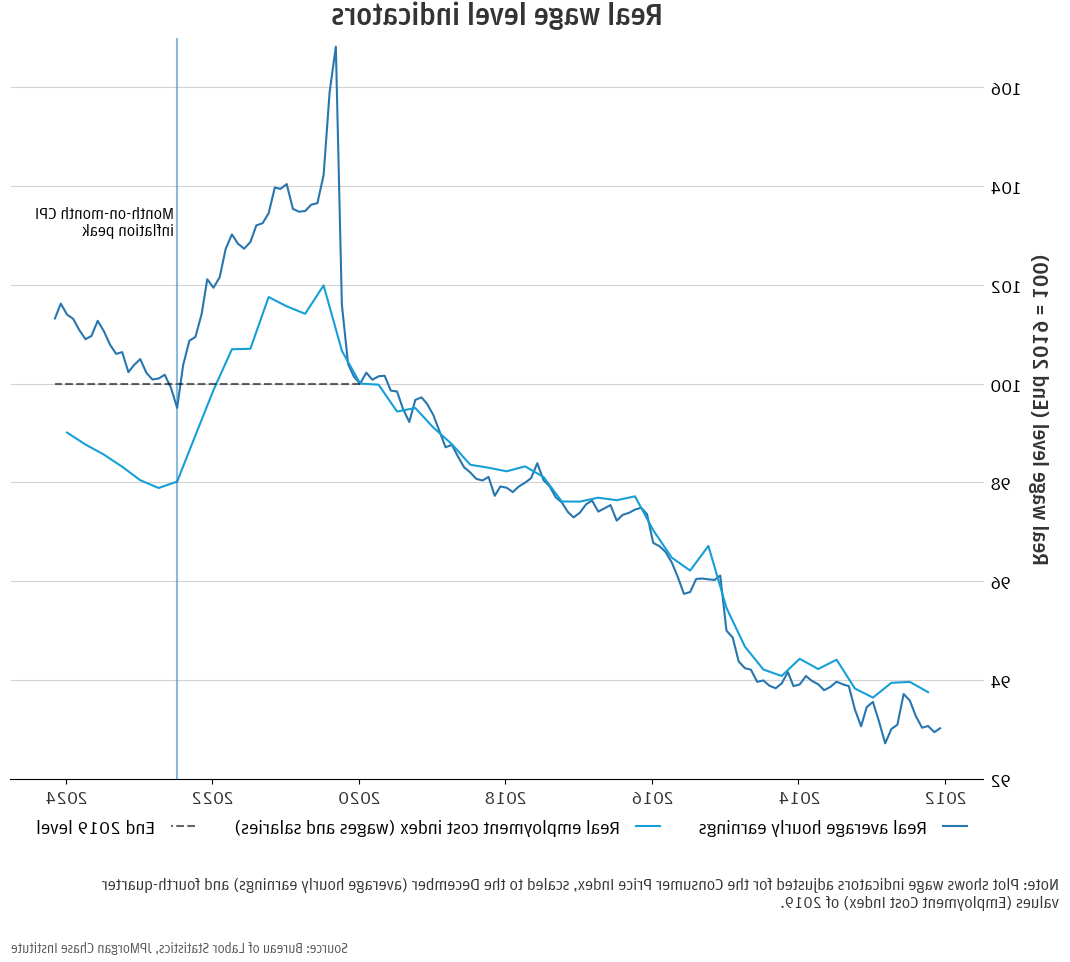

有了这个先例, maybe it’s not surprising that there are a range of views as to how real income growth has been performing. 较短的时间跨度更容易:过去一年, 主流指标指向实际收入增长. 但在covid -19引发的劳动力市场波动之后, 财政刺激计划, and inflation—it can be hard to know where exactly workers stand relative to a more stable benchmark predating the pandemic-era disturbances. 让我们把重点放在一些客观指标上,以此来巩固想法. 两份政府发布的工资数据(注:劳动力价格), 不是劳动收入, 工资*数量)是多少 平均时薪 (AHE)和 工资和薪金雇佣成本指数 (ECI). The former is released monthly and changes with the composition of jobs (a spike in AHE in early 2020 coincided with layoffs in lower-wage service jobs), while the latter is a “cleaner” measure of within-occupation compensation change released quarterly. The figure below shows the two nominal series after dividing by the Consumer Price Index and scaling to their end-of-2019 values.

图1:两项衡量实际工资趋势的指标(FRED地块链接)

哦,天哪,一个系列说我们过得更好, 另一个则相反(比较), 这已成为常态, 到2019年的基线). 让人困惑! 这两个系列都表明,我们低于大流行前的趋势, 至少根据眼球和最合理的选择开始/结束点进行外推. ECI保持职业不变,所以可能有一个提升技能的故事.e., 也许普通工人已经迁移到价值链的上游,从事工资更高的工作, 推高了AHE,却把岗位内ECI抛在了后面. 如果没有更多的数据,我们无法直接判断, but a within-person perspective from earlier 研究所 analysis (discussed below) provides one lens.

与12bet官方的内部措施保持一致. 一个研究所 报告 从几年前的情况来看,大流行前的情况也类似:2015年之前的增长较低, 然后随着劳动力市场收紧持续到2019年,情况有所好转. 值得注意的是, the following two plots on income dynamics differ from usual publicly available sources in that they center on take-home pay and use a broad measure of income that includes inflows from government programs like Unemployment Insurance and Economic 影响 Payments.

Figure 2: Pre-pandemic view on income growth shows lower-income groups benefitted most from labor market tightening.

我们最近的 购买力报告 provides a lens on “where we are now” (or at least as of August 2023) comparing individuals’ take-home income relative to their late 2019 level. 图3显示了跨收入四分位数的情况, 人们的实际收入比2019年底高出1 - 6%. Lower-income individuals are on the higher end of the range—a distributional outcome consistent with 最近关于这个主题的其他研究. Aggregating across about four years, this is an annualized growth rate difference of between 1 and 1.5个百分点,大致与2020年之前的增长差异一致. 有趣的是, 然而, 这种分离发生在2021年底,也就是当年年底, 财政刺激对收入的直接影响已经减弱, 但收入较低的个人维持了他们的相对收益. 有效地, 我们的数据显示,在该系列的最后两年,这一趋势没有取得任何进展, 尽管失业率仍然接近50多年来的最低水平. 值得注意的是, the timing of relative income trends in our data does not align with the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker, 这也提供了工资四分位数的突破. 这在一定程度上是因为这些数据的使用 12个月增长率的12个月滚动平均值,因为现行人口调查数据的样本数量有限.

图3:随着时间的推移跟踪个人显示出四年来适度的实际收入增长, 在消除衰老的影响后,哪些转化为最小的增长.

我们2019年至2023年的数据是否与劳工统计局的指标相当? 有点像,但只有经过下面的变换之后. The growth measure we’ve used in 研究所 报告s is a within-person concept—which is great when you’re concerned with the experience of actual households—but it means we’re tracking a population that is getting older as we watch them walk-up their career ladder. 学术 研究 implies that may bias upward our growth measure by over 1 percentage point per year for people in their early-to-mid-forties (close to our sample average) relative to labor-market-wide data. 从2019年到2023年,我们的增长分布中心约为3%到4%, 实际收入增长比之前的时期要慢, and—depending on expectations for life-cycle growth—might line up with the less-optimistic signal from ECI at about 99 percent of the December 2019 value.

虽然这不是一个很好的结果, 过去几份就业报告的净工资增长表明,经济增长超过了通货膨胀, 尽管 2月份的软数据这可能最终会弥补早先经通胀调整后的损失.

This material is a product of 12bet官方 研究所 and is provided to you solely for general information purposes. 除非另有特别说明, any views or opinions expressed herein are solely those of the authors listed and may differ from the views and opinions expressed by J.P. 摩根 Securities LLC (JPMS) 研究 Department or other departments or divisions of 12bet官方 & Co. 或者它的附属机构. 本材料不是JPMS研究部门的产品. 消息来源被认为是可靠的,但12bet官方 & Co. 或其联属公司及/或附属公司(统称为J.P. 摩根)不保证其完整性或准确性. Opinions and estimates constitute our judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. 不应就任何计算作出任何陈述或保证, 图, 表, 本材料中的图表或注释, 哪些只作说明/参考用途. The data relied on for this 报告 are based on past transactions and may not be indicative of future results. J.P. 摩根 assumes no duty to update any information in this material in the event that such information changes. The opinion herein should not be construed as an individual recommendation for any particular client and is not intended as advice or recommendations of particular securities, 金融工具, 或者针对特定客户的策略. This material does not constitute a solicitation or offer in any jurisdiction where such a solicitation is unlawful.